In recent months, the US stock market has pushed to new highs despite facing significant headwinds. At first glance, this might appear to be a sign of a robust economy and supportive policies, but the reality is more complex. The question worth asking is whether the rallying stock market truly represents the state of the US economy and, importantly, the consumer. The old saying that “the stock market is not the economy” is proving especially relevant, with a growing disconnect between buoyant equity markets and an economy dealing with inflationary pressures and weakening fundamentals. With such a tech-heavy market, and given the increasingly muted response to tariff headlines, it is timely to explore what is really driving this divergence.

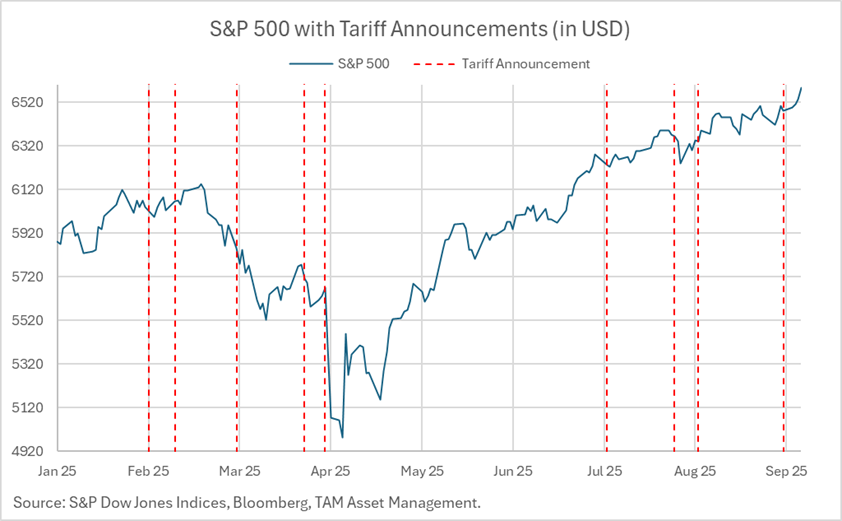

In the early stages of the trade war, tariff announcements often triggered sharp selloffs across equities as investors braced for worst-case scenarios. However, over time a repeated pattern developed in which threats were softened, delayed, or reversed, leading to the term “TACO trade”: Trump Always Chickens Out. This embedded scepticism has reshaped investor behaviour. Today, when tariff headlines break, the knee-jerk sell-off is more contained, volatility fades more quickly, and more market-sensitive assets hold their ground. The market has effectively factored in a belief that the political bark is worse than the economic bite. The consequence is that stock market movements have become less sensitive to tariff risks than underlying economic realities might warrant, muting the downside reaction but simultaneously contributing to a growing decoupling between Wall Street and Main Street.

It is one thing for the downside to be less pronounced, but what explains the considerable upside? The below chart may provide some indication.

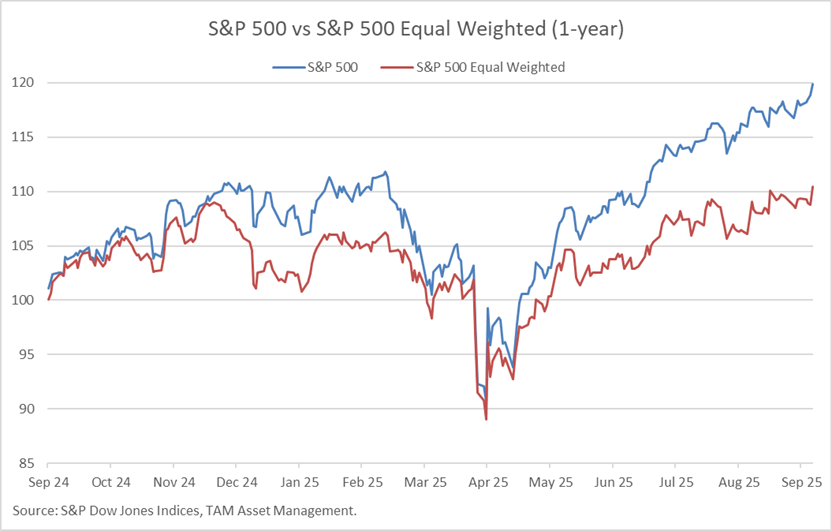

The answer lies in market concentration. The chart above comparing the S&P 500 against the S&P 500 Equal-Weighted Index makes this very clear. The standard S&P 500 weights companies by market value, meaning the largest firms carry the greatest influence on performance. By contrast, the equal-weighted version gives every company the same 0.2 per cent weight, regardless of size. In other words, it reflects how the ‘average’ stock is doing, rather than being dominated by the very biggest firms. Over the past year, the traditional S&P 500 has surged, while the equal-weighted version has lagged significantly. The reason for this gap is that a small group of companies have been driving the majority of the gains. These are the so-called Magnificent 7: Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, NVIDIA and Broadcom. Together they now account for roughly 34 per cent of the index and dominate its earnings profile. Their strong performance has pulled the overall market higher, but when you strip them out, the average stock has seen far more modest returns. The takeaway is that headline market strength does not necessarily reflect broad corporate health, but instead the extraordinary weight and influence of a select few firms.

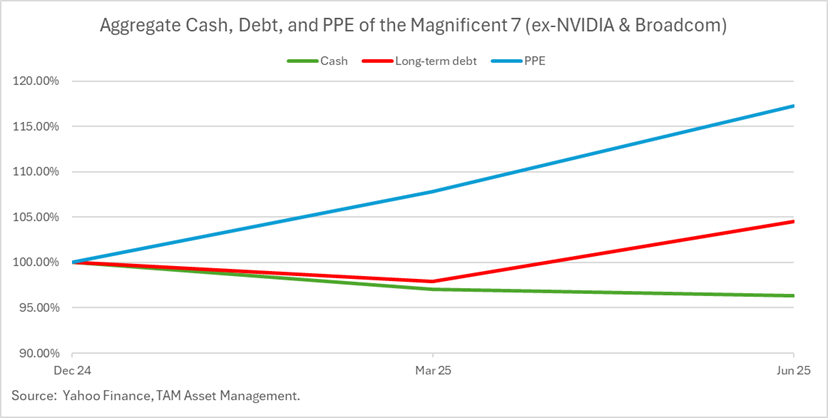

A closer look at the balance sheets of the Magnificent 7, with the exception of NVIDIA and Broadcom, helps explain how this leadership has been sustained. These two are excluded because they operate much leaner business models as fabless companies, meaning they design chips but outsource the actual manufacturing and production offshore. As such, their balance sheets look very different to the others, with unusually large cash holdings that would otherwise distort the broader picture, particularly when assessing changes in long-term borrowing. For the remaining five firms, the last two quarters show a clear trend: cash levels have fallen by around 3.7 per cent, long-term debt has risen by 4.5 per cent, and capital expenditure on property, plant and equipment (PPE) has jumped by an impressive 17.3 per cent. In plain terms, these companies are running down cash and borrowing more in order to fund massive spending on data centres, chips, and AI infrastructure. Their scale and willingness to invest has driven earnings growth and supported share prices, and other firms have been compelled to follow suit to avoid falling behind. This wave of investment is largely self-reinforcing, generating growth that does not yet rely on higher consumer demand but instead on the aggressive capital spending of the companies themselves.

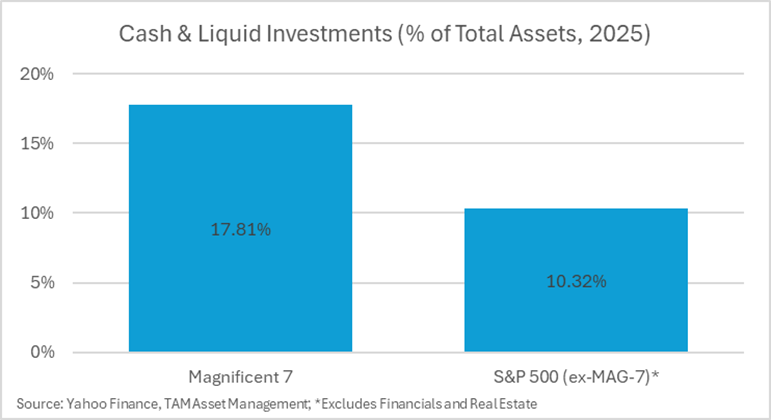

The capacity of these companies to sustain this strategy is underpinned by their exceptionally strong liquidity positions – that is, the amount of cash or investments that can easily be turned into cash. Across the S&P 500, excluding financials and real estate due to their different accounting practices, total cash and liquid investments amount to around $1.85 trillion. The Magnificent 7 account for roughly 24 per cent of this pool, even after the recent drawdowns, holding about $450 billion in cash-like holdings. On average, their cash represents 17.8 per cent of total assets, compared with only 10.3 per cent for the rest of the index.

This substantial liquidity cushion provides them with ample scope to continue funding investment, either directly through cash reserves or by taking on additional debt. While at some stage these AI investments will need to deliver measurable returns, the balance sheet strength of the Magnificent 7 means there is no immediate pressure for that to happen, allowing the cycle of investment-led growth to continue for longer.

Set against this corporate strength, the broader economic picture is more mixed. Recent US jobs report data showed fewer jobs added than expected, unemployment nudged higher, and inflation continued to drift upwards, albeit in line with forecasts. The Federal Reserve is now overwhelmingly expected to cut rates, with market pricing assigning a near-absolute probability of a 0.25% cut. Our discussions with industry experts, who hold extensive coverage of the US economy, sense that consumer sentiment remains resilient, supporting a moderately constructive view of US growth.

In summary, the US finds itself with a two-story economy: a stock market led higher by a handful of tech giants with formidable balance sheets and the ability to sustain heavy investment, and a real economy that is progressing more tentatively under the weight of tariffs, inflation, and slower job creation. For investors, this means that market strength cannot be taken as a straightforward signal of economic vitality, but rather as evidence of the concentration of corporate power and resilience in a select group of firms. Nevertheless, provided that tariffs do not ignite a sharper inflationary cycle and with rate cuts on the horizon, there remains a clear case for maintaining exposure to US equities within diversified portfolios, even while recognising the underlying divergence between Wall Street and Main Street.

DOWNLOADS

Wall Street Vs Main Street

Wall Street Vs Main Street