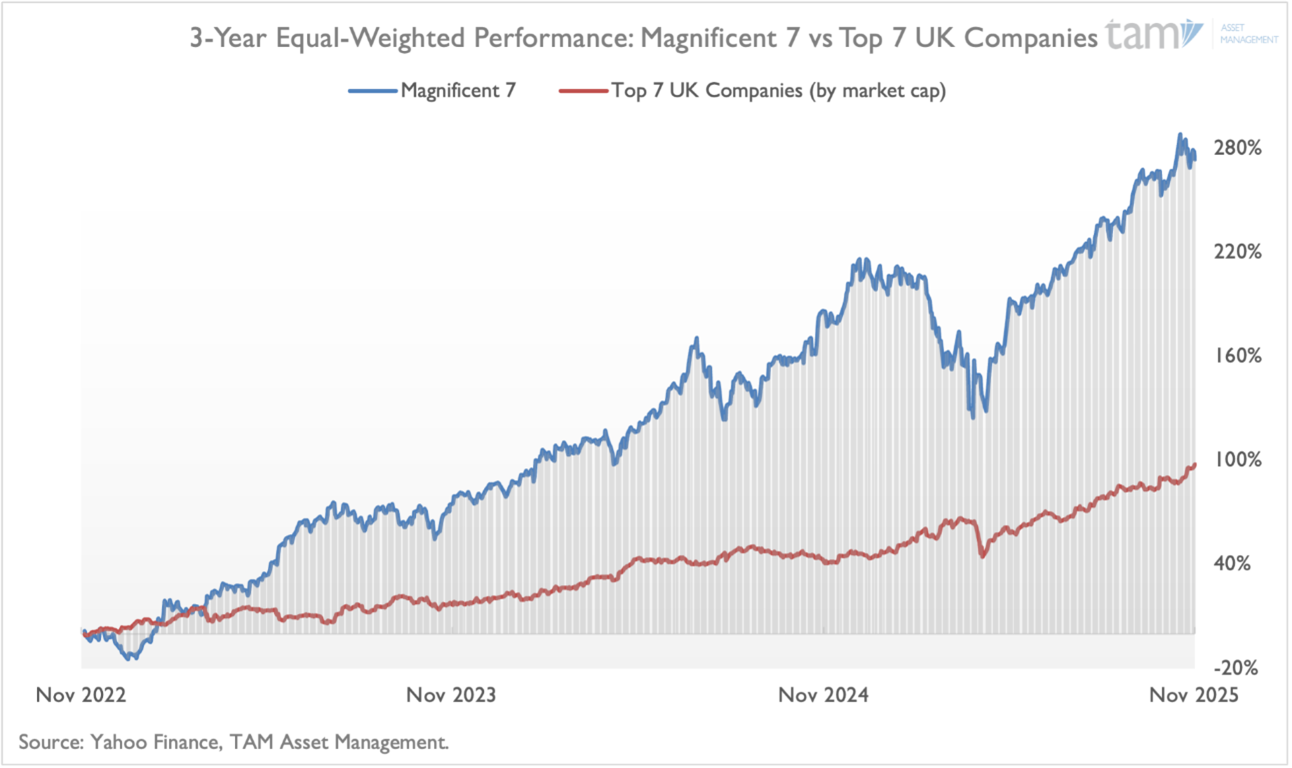

The last few years have made one contrast impossible to ignore: while the United States continues to power ahead through innovation and the rise of the “Magnificent 7”, the UK equity market has fallen further behind – with not even a “Magnificent 1” to point to. The chart below illustrates the point clearly. Over the past three years, the Magnificent 7 have delivered remarkable gains, while the seven largest companies in the FTSE 100 have seen far more modest returns. The gap reflects more than just performance; it reflects a structural difference in how each market creates, scales, and rewards growth.

This divergence has had real consequences for global asset allocators. The UK’s share of the MSCI World Index has declined from around 10% twenty years ago to just 4% today, largely due to years of relative underperformance. As global indices shrink the UK’s representation, benchmark-aware investors allocate even less to it. This becomes a self-reinforcing cycle: weaker performance → smaller index weight → lower allocations → weaker performance.

With the UK Budget approaching on 26 November, the question now is whether policymakers can break this cycle and set the country on a firmer long-term growth path.

Structural Headwinds

One structural headwind to UK growth is low retail participation. A 2024 Hargreaves Lansdown survey found that, outside of workplace pensions, only 23% of Brits have invested in the UK stock market, compared with nearly two-thirds in the US. The gap was attributed to a higher willingness to take risk, cultural differences and better incentives in the US.

An ageing population adds to this challenge. As the proportion of older people rises, so too does the demand for lower-risk products such as money-market and fixed-income instruments, reducing broader equity market participation. A smaller domestic retail base means fewer “sticky” long-term holders of UK shares. As a result, the ownership base for UK stocks is heavily dependent on foreign capital, which can be more flighty and volatile.

Against this backdrop, there is speculation that the upcoming Budget could seek to nudge more UK savers into equities. One idea reportedly under consideration is a reduction in the annual allowance for Cash ISAs from £20,000 to around £12,000, while maintaining the full allowance for Stocks and Shares ISAs. The intention would be to broaden the domestic investor base for UK capital markets and to encourage savers, where appropriate, to seek higher long-term risk-adjusted returns through investment rather than relying predominantly on cash.

However, the impact of such a move may be more limited than it appears. Investors could simply redirect their allocations to non-UK equities, diluting the intended effect. The UK could, though less likely, pair this reform with a “Brit ISA,” originally proposed by the Conservatives. A Brit ISA would create an additional £5,000 annual tax-free allowance on top of the existing £20,000 limit, with the condition that the funds be invested solely in UK-listed equities and assets. Although Labour initially scrapped the proposal, it could resurface if the government seeks stronger measures to revitalise domestic equity ownership.

Another structural challenge is the UK’s difficulty in scaling innovative companies at home. While the UK produces strong early-stage innovation, many companies look abroad when seeking deeper pools of capital and higher valuations. A recent PwC report showed that, by the end of Q1 2025, UK-headquartered companies listed in the US had a combined market capitalisation of around $2.2 trillion (roughly £1.7 trillion) – almost equivalent to the entire FTSE 100 at £2.1 trillion. In other words, a significant share of Britain’s most valuable businesses is listed overseas. This weakens the UK market’s ability to generate home-grown champions and further reduces its weighting in global indices.

The upcoming Budget

With the UK budget quickly approaching, there is a real opportunity for an inflection point in the UK’s subdued growth story. However, it won’t be easy. The trade-off ultimately comes down to how far Rachel Reeves is willing to go to support future growth, set against the political constraints of maintaining fiscal credibility and preserving Labour’s prospects of re-election.

The starting point is challenging. Independent estimates suggest there is a fiscal gap of around £30 billion to be closed if the government is to deliver on its spending ambitions while still meeting fiscal rules. This gap needs to be plugged to avoid adding further to the national debt. A higher and rising debt burden can increase the perceived risk of lending to or investing in the UK, prompting investors to demand higher returns. In turn, this raises borrowing costs and can act as a drag on economic growth.

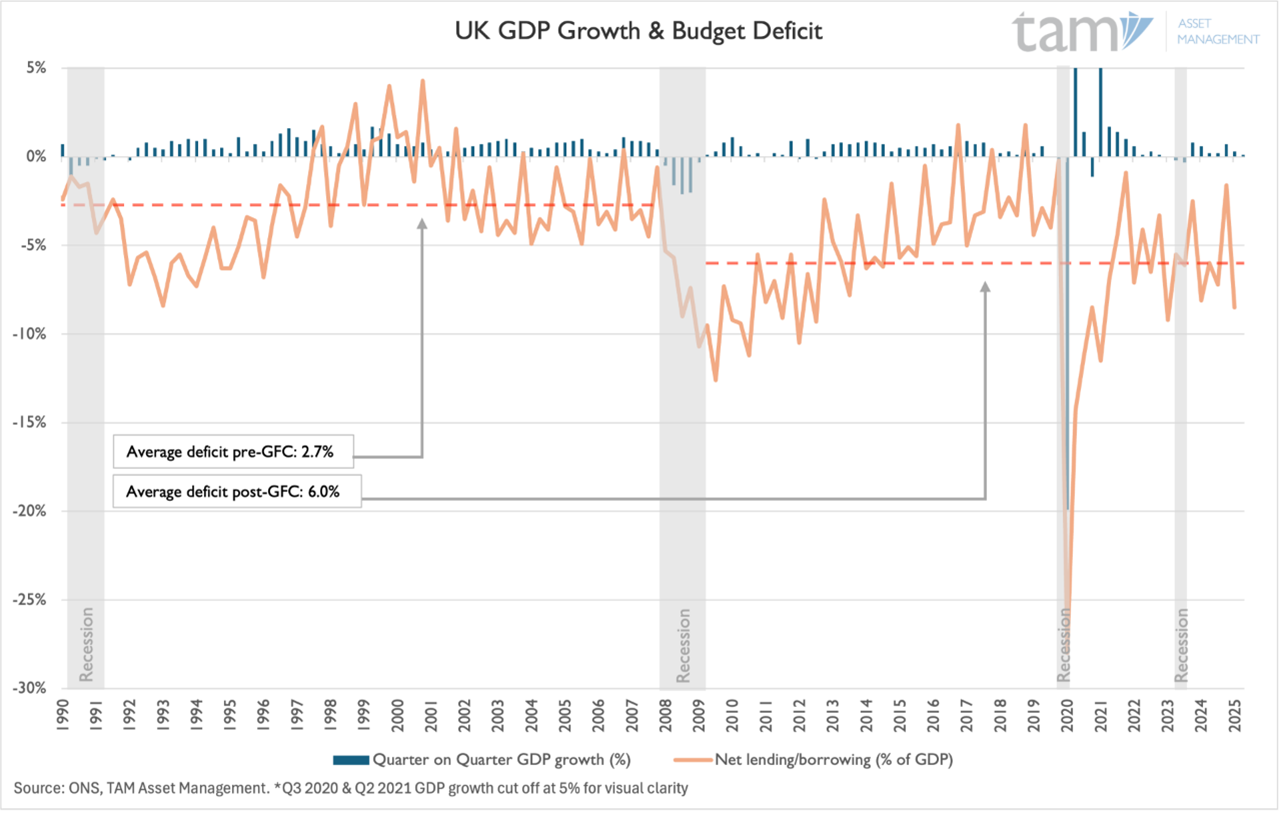

As shown in the chart below, the UK budget deficit – the difference between government spending and tax revenues – averaged around 2.7% of GDP from 1990 until just before the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Since the GFC, it has more than doubled to an average of about 6%. Over the same period, average quarterly GDP growth has edged down from 0.6% to 0.5%. In other words, the UK has run budget deficits more than twice as large on average since the GFC, while growth has actually been slightly weaker.

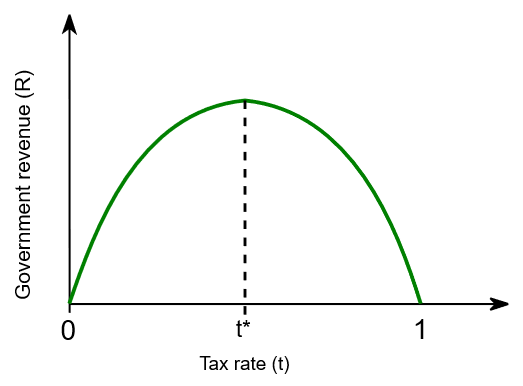

In this context, any attempt to close the deficit by raising taxes runs into an important piece of economic theory: the Laffer curve. Proposed by Arthur Laffer in 1974, the Laffer curve suggests there is an optimal tax rate (t*) that maximises tax revenue. Below this rate, tax increases tend to raise revenue. Beyond it, however, higher rates can begin to reduce the total tax take by disincentivising work, investment, and economic activity, or by encouraging capital to move elsewhere.

Many UK fund managers we speak to have speculated that we could be near this optimal tax rate currently, and that with any increasing tax rates it would only encourage capital flight and thus decreasing overall tax revenue. Therefore, the options for Labour remain problematic.

Market reaction will largely depend on how tight or generous the Budget turns out to be. If it is tighter than investors expect, with a clear plan to get the public finances on a more sustainable footing, that would likely be helpful for UK government bonds, slightly supportive for sterling and reassuring for those who value long-term stability – though it could mean slower growth in the short term. If it is looser than expected, with more emphasis on extra spending or delaying difficult decisions, the economy might get a short-term lift, but at the risk of higher government borrowing costs and renewed pressure on the currency. It is a fine balance, and markets will be watching closely.

Where we sit

While the debate over the UK’s long-term trajectory continues, TAM remains dynamically allocated so that we can pick up on the best opportunities wherever they present themselves. Despite the gloomy picture for UK growth at an index level we prefer to access UK opportunities indirectly through global fund allocations, allowing us to benefit from deep expertise and highly active stock selection.

For example, within the Active model range, Lansdowne Developed Markets is a fund we currently hold which has a sizeable c.40% allocation to UK equities and has delivered strong outperformance versus global indices, demonstrating that attractive opportunities can still be found within the UK market when approached selectively and through the right managers. The same principle applies across our other model ranges, where our diversified approach continues to capture attractive UK exposures while maintaining global diversification.

The UK faces genuine structural headwinds, from low retail participation and an ageing population to the leakage of innovative companies overseas. The upcoming Budget offers a chance to address some of these issues – whether through measures to deepen domestic capital markets, improve incentives for investment or chart a clearer path for the public finances. Doing so, however, will require navigating the tension between economic necessity and political reality.

Recent years have underlined the gap between the US, with its “Magnificent 7”, and a UK market still searching for even a “Magnificent 1”. The Budget will not close that gap overnight, but sensible policy could help lay the foundations. Regardless of the policy outcome, TAM’s diversified and dynamic approach means client portfolios remain exposed to the best ideas globally, while retaining the flexibility to capture selective opportunities in the UK where the risk-reward is compelling – and to participate if and when the market finally produces its own “Magnificent 7".

DOWNLOADS

The UK's Not-So-Magnificent 7

The UK's Not-So-Magnificent 7